Play It and Pass It On - An Interview with John Knowles

Play It & Pass It On

An Interview with John Knowles, CGP

This article was originally published in the Fall 2015 issue of the Fingerstyle Guitar Journal. To receive fingerstyle guitar interviews, workshops, reviews, and more automatically each quarter subscribe to the Fingerstyle Guitar Journal

The sound of a church choir, the buttons on an accordion and the plucking of the strings on a plastic ukulele were John’s first tactile and aural experience with music. Then at the age of thirteen he discovered the guitar and the music of Chet Atkins. This had a profound impact on John. Though he didn’t know it, the course of his future was taking shape.

When it came time for John to enter college he soon discovered that the academic community of the 1960’s was not very accepting of the guitar – John then turned his focus to physics and mathematics, earning his PhD in physics from Texas Christian University in 1968. John entered the work force at Texas Instruments working in their research lab. After two years his musical muse came calling. Though it was against conventional wisdom, John made the bold decision to follow his heart and devote his life to music.

In the years since, John has worked with such legendary guitarists as Chet Atkins, Jerry Reed, Lenny Breau, The Romero’s and Tommy Emmanuel. In 1996 Chet Atkins awarded John the first honorary CGP (Certified Guitar Player) degree and in 2004 John was inducted into the National Thumb Picker’s Hall of Fame. Through his many publications John has taught a new generation of guitarists the music of Chet, Jerry and Lenny.

Today he is focused on recording a new project with Tommy Emmanuel, performing and occasionally giving a master-class as he recently did at Berklee School of Music.

I’d like to talk with you about your early days in Texas, your first influence from music and a little about your family.

My dad was a preacher so I was always around church. We sang all the old Protestant hymns like “I Come To The Garden Alone.” It was a big enough church that we always had a good choir and I would watch them rehearse each Thursday night. It amazed me they could take out each part and put them back in. On Sundays I would travel around the congregation sitting next to people looking to hear the different parts. So voice leading has always been fascinating to me. I didn’t know the names of the chords but I certainly had the desire to learn the parts. I remember everyone in the church thinking how sweet little Johnny was because I would go sit with everybody. They didn’t realize I was auditioning them!

Dad had a huge classical record collection that I grew up hearing. My mom loved country music so I’d hear that on the radio. Dad had a couple of uncles who loved music. Uncle Red served in World War II and was aware of Django Reinhardt, so I heard about a lot of different music early on.

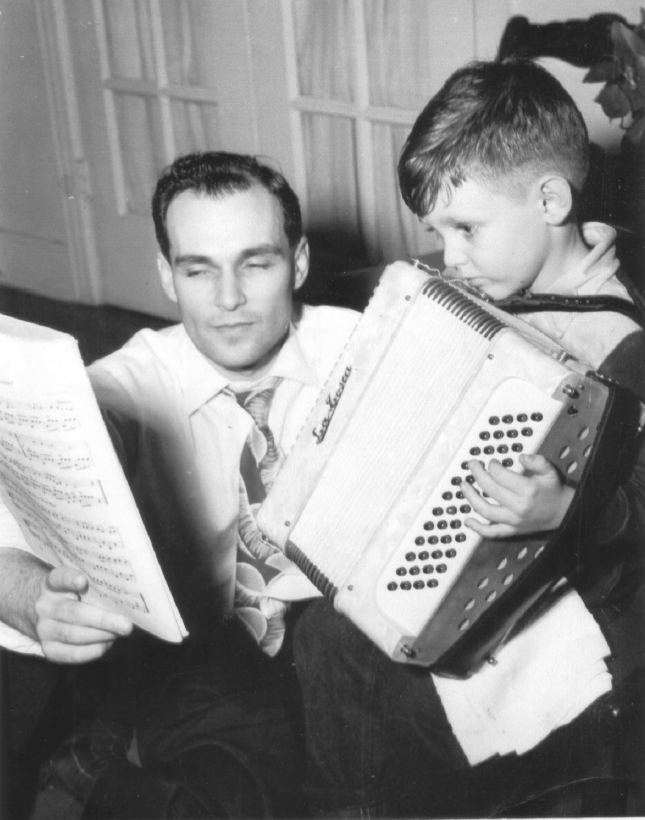

By the age of six I started taking accordion lessons. We didn’t have room in the house for a piano and the accordion was the hip thing to do back then. In fact it was hipper than the guitar back in the day. (laughter)

Because the buttons on the accordion are arranged like the circle of 5ths, I kind of learned how harmony is arranged. So without setting out to do it, I learned the basics of how harmony is organized. Being able to see the keyboard, you learn how to make your way around scales and melodies. So before I ever touched a fretted instrument I could read music. I had a rich heritage of listening to music. I was surrounded by people who encouraged me and loved music. It would be hard to complain about any of that.

Mom’s brother, Uncle Arthur, could play a few things. He had an old Gibson and lookin’ back it was probably a Kalamazoo model. It was one of the guitars you’d buy through Sears back in the day. He would sing, “My wife and I lived all alone, in a little log hut we called our own. She liked coffee and I liked tea – together we lived happily.” He’d laugh when he got to the chorus, “Oh, ho, ho you and me, little brown jug how I love thee!” I thought man, that’s the new benchmark! He was also into electronics and that interested me as well, so I hung out with him a lot. I think he’s the one who convinced me to try the ukulele and later the guitar.

Do you feel it was an advantage to play other instruments before the guitar?

Yes. My initial effort on the ukulele was to transpose what I learned on the accordion. I could see the keyboard of the accordion and I knew the next fret up on the ukulele must be like playing a black key. I started mapping out intervals and chords. I had to decode it because, as they put it, my plastic ukulele came with all three chords! I knew there was more.

What do you remember being the first harmonically rich music you heard?

I guess it would have been the Bach Chorales I heard as a kid. I also heard things like “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” with all those great harmonies. I mentioned my dad’s record collection; he loved the impressionists so I heard Debussy and Ravel. I also grew up listening to Brahms symphonies. I think the first time I got hip to any jazz sound was when I discovered Johnny Smith through a friend who had a few of his records. In the early days I would have heard Johnny Smith and a few Chet records. I also heard Les Paul and Mary Ford on the radio. At that time they were making hits.

None of my friends played the guitar at that time. It wasn’t until I was in high school that I knew anyone who played the guitar and that was in Houston, Texas! It wasn’t like I was out in the boonies. By the time Elvis came out I was already playing barre chords I thought, “He’s no fun He doesn’t even play barre chords!” (laughter)

Since you brought up Johnny Smith please share your story about taking a lesson with him.

When I was seventeen or eighteen, Dad announced that the family was going to take a ski trip to Colorado Springs for Christmas. My first thought was, “That’s where Johnny Smith has his music store.”

So I wrote him a letter and asked if I could take a lesson. He opened his store on a Sunday and spent a couple of hours with me. He asked me questions and had me play things for him. Chords, voicings, scales, stuff like that. As we went along, he made notes about things I needed to learn. So the lesson was basically an inventory and a to-do list. I realize now that he was guiding the next steps in my learning but he was counting on me to do the work.

He played a little bit but it was mostly a conversation about music. I remember that he treated me like a fellow musician. And I remember how smoothly he moved on the fingerboard.

When my dad came by to pick me up, he wanted to take a picture but Johnny said he hadn’t shaved. When dad asked him about paying for the lesson, Johnny said he wouldn’t charge me because we didn’t really do that much.

Over the years, I’ve heard several players describe similar encounters with Johnny. And I’m not the only one who ever heard the “I haven’t shaved” excuse.

Access to material and the opportunity to see people play is certainly different today than when you began playing.

That’s true. In the early days you really couldn’t see many musicians on television. You had to depend on recordings and your ear.

I soon learned to play music with my eyes closed so I could concentrate on what I was hearing. I would then name and number the notes as I learned them to help organize and remember what I was playing. Eventually when I had the chance to study music theory I was kind of primed for it. There has always been a puzzle solver in me. I want to figure it out – if I can do it here, how can I do it there? I remember years later Jerry Reed once said, “The guitar is just options, lots of options.” I thought yeah, that is the gospel!

Having a curious mind is a great thing and you obviously have that.

If I have some gifts it would be a natural curiosity and a love for listening to music. Another would be that I don’t frustrate easily. It has never bothered me that I couldn’t do something yet. I remember the first time I heard Chet. I thought, that’s impossible! Then I thought, well it couldn’t be impossible because he’s doing it.

After about thirty seconds I said, okay let’s roll up our sleeves and get to work. I have always had a confidence factor that I would get it eventually.

I believe people can be overwhelmed when listening to accomplished musicians because they are looking at the whole picture. They haven’t developed the ability to focus on the individual parts.

Yes, but I think a good players objective is not to have you think about the nuts and bolts, it’s to touch and delight you. As a matter of fact, over time I’ve had to learn to turn off my analytical inspector guy and just be able to dig music.

Well I’ve certainly been accused of that.

Don’t get me wrong I’ve still got a bad case of it. (laughter) Evidently it’s chronic, it doesn’t go away. But there is also pleasure in understanding how music is put together and where it’s going. To some that would be a chore but to me that’s the pleasure. It’s like if you’re somebody who cooks and you have a good meal, you say, “I wonder what seasonings they are using?” Me, I don’t know, I just eat it. (laughter)

What intrigues you these days in your pursuit of music?

Well I’m always looking for something new. Along the way I’ve learned to listen to people who are artists but not necessarily musicians. I’ve hung out with theater people, filmmakers, and choreographers. The way they create and put things together is different than a musicians but the end result is not that much different. Songwriters here in Nashville are also high on my list. Songwriters are trying to tell a story and theater people also have that story-telling impulse. They’re trying to capture emotions with lighting and things like that. So when I’m arranging let’s say “The Nearness Of You,” I’ll look at the lyric and to me that song is not being sung at 11:15 in the morning. It’s being sung at midnight. The moon is out and nobody is in the room but two lovers It’s a setting. If it were a film you’d know what it would look like. This tells you where there is drama and tension so you choose the harmony and voice leading that will set that up, It’s more than what chord do I play? Of course you have to know the chords and the melody, but it’s much more than that. There is a story to be told, a moment to be captured.

I hear people from time to time use this phrase “chord melody,” that’s a mystery to me. I’ve never thought, play some chords and find the melody on top. That’s just not how I do it.

I’ll share a story with you that will reflect how I think when arranging. We had been down to New Orleans visiting our daughter soon after she had moved there. I remember hearing a saxophone player down on the levy by the French Quarter playing, “Do You Know What It Means To Miss New Orleans.” About three months later Katrina hit and all of a sudden that melody had a new meaning. I went back and listened to Louie Armstrong’s version on iTunes. It had a little piano vamp that I stole but I made it darker harmonically. I also made things a fret off because after a big storm like that I figure nothing is where it used to be. I even went so far as to take the bridge up a half step through the first half. So everything is kind of dislocated as a way to capture the feeling of where the city was at that time. On the second half of the bridge I move back down to where it was originally written. You almost don’t know it if you don’t know it. (laughter) It’s true, people who don’t know it won’t know it and I don’t care I do care however that I’ve done something that affects the experience for the listener. It’s like going to the movies, people don’t notice the lighting but the lighting guy did Oscar level work. That’s his job and this is mine.

There is a philosophy that art cannot live in a bubble and your stories on how you create music remind me of that.

In one of the old films of a Segovia class there is a guy from the states playing a Spanish piece and as he plays Segovia kind of backs up as if he’s going to get something on him. Finally he reaches over and puts his hands on the strings to stop him from playing and says, perhaps you should take a walk in the countryside, maybe have a little Spanish wine, perhaps look into the eyes of a young woman and then play this piece again. (laughter)

If we only reveal what we’ve learned in the practice room, it’s not cool and not all that interesting. But if we use what we’ve learned in the practice room to reveal what we’ve lived and what we care about now, that’s cool.

I think that’s why no matter how complex you may be as a musician you can still be touched by Hank Williams or Lightin’ Hopkins.

Absolutely! That’s true and no matter how complex you may get it’s important not to overlook that. Another thing is not to use everything you know in one tune. We all know too much for any one moment. Save some for the next tune. I used to watch Chet figure out stuff from Lenny Breau, but he just used part of it for an intro, turnaround or variation. He would sprinkle it around so he still sounded like Chet, but with a little something extra.

We’ve all heard the musicians that play every lick they know in one chorus.

Yeah, I’ve always thought it was best to forget about the guitar players in the audience and play for their sweethearts instead. If they enjoy what you’re doing you’ve really accomplished something.

Well a lot of musicians would be listening and thinking, I would have played that different; I would have played it faster, why did he play it in that key? It’s that musical horse race mentality that I can’t stand.

When I first came to Nashville I realized that I was surrounded by more good guitar players than I even knew existed. At first it really freaked me out, but then I thought, I’m the only one with my viewpoint, I finally just let it slide. That gave me complete freedom to respect and admire what everyone else was doing without it being a commentary on what I was doing. I don’t mind being in a room with someone that overwhelms me as long as I’m doing what I do well.

One of the things that I love about playing with Tommy Emmanuel is that he is so clear about being Tommy. He leaves all the room in the world for me to be John. In the process we get something special, which is us together. I also love being on stage with him because I’ve never been on stage with anyone who is so confident and respectful of the audience. He also listens so well that there is no danger. He’s a great player and a great listener. People ask me, aren’t you afraid to be up there with him? I say, are you kidding, it’s the safest place to be. He loves doing it and he’s happy I’m there. What more could you ask for?

I once told him that it’s much easier to play with him in public than it was with Chet. He quickly said, “That’s because he was our daddy, you and I are brothers!”

Let’s talk about the first time you met Chet and the development of your relationship.

When I first met him it was at the symphony in Dallas. A friend and I went to the rehearsal. Chet was so relaxed and off the cuff that I forgot he was my hero. Before long we were talking about this and that and then he handed me a guitar and said, “Well show me what you’re working on.” So I started playing what I was working on which was “The Entertainer” from the movie The Sting. Chet said, “Finish that up and send it to me.” When we walked out my friend said, “John you just played for the man!” To me it just felt like I got to hang out with somebody that I had grown up with.

For the most part I was always relaxed around Chet, but every now and then I’d think, that’s the guy on the album cover! It would only be for a moment because he would not be doing anything to make himself look amazing. Chet just did amazing work.

He also did very ordinary things. I remember one time we went to lunch and then stopped by a hardware store. He bought some lights bulbs because he was going to change them at one of his rental properties; I think it was Mercury Records. It had kind of a high chandelier so Chet got a ladder out of the closet, climbed up and started changing the bulbs. He then leans over and says, “Do you have a good grip on the ladder? Don’t drop me, I’m a legend, you’ll have a lot of explaining to do.” (laughter)

I think there is something about doing chores that always felt right to him, he grew up doing chores. I think doing normal stuff reminds you that you’re just a normal person.

How did you meet Jerry Reed?

That was through Chet. He had heard some songs I’d written and said, “Write some more songs and I’ll show them around.” I knew he was producing Jerry so I wrote a tune called “Red Hot Picker.” At the time I didn’t know Jerry wrote most of his own material but he liked it and recorded it! I thought, Well, this is some business! But when I moved to Nashville I found out it’s a little harder than that.

I remember watching Jerry play a lot of his instrumentals and by then Chet was recording many of them. This would have been in the late ‘70s. I thought, I’ll learn some of them and write them down so people could see what Jerry was up to. But Jerry wouldn’t show me how to play his tunes. He said, “Well did Chet show you how to play his stuff?” I said no, I was in Texas. He said, “Well I ain’t showing you anything. You learn them and show me and I’ll tell you if you’re right.” (laughter) So I got to work and would get together with him and play things for him. Jerry would say things like, “I know I didn’t do that.” He also said things like, “If it were that hard I wouldn’t have done it. There must be an easier way.” Then he’d show me what he did. Then it was like buttermilk to play. His stuff was about knowing how to put great ideas on the fingerboard in an effortless way. His knowledge of the guitar and his ideas were melded together in a way that I had never seen and haven’t seen since.

Guys like Chet, Jerry and later Lenny were all one of a kind. I remember when I met Lenny

Chet called me and said, “Lenny Breau is in town! I didn’t know if he was dead or alive. I haven’t seen him in years. You got to get down here!” So I went down there and hung out. We had a spare bedroom so I let Lenny stay with us until he got a place. So for days we hung out, talked and played. I had heard his first two records but had no idea what he was doing until I saw him play.

Lenny was one of the deepest and greatest players to ever live. Did you gain any insight to him while spending time with him?

Well, Lenny is really hard to summarize. When he was just a kid he was learning entire albums by Chet in a matter of days while the rest of us were struggling to learn one lick. He then met the jazz pianist Bob Erlendson, who began teaching him the foundations of jazz. When I was around Lenny he was always listening to music. He had a suitcase full of cassette tapes. He would listen a lot to John Coltrane, McCoy Tyner and Bill Evans.

Here is a funny story about Lenny It was summertime and he was staying with us. He always walked around in an overcoat that he carried his Walkman and cassette tapes in. He would sit by the swimming pool in his coat with his headphones on while everybody else was wearing bathing suits. I said, “Lenny I could loan you a bathing suit if you want to swim.” He said, “No, I don’t think so, I’d get my tapes wet.” (laughter)

I remember when Lenny had just gotten into town. Chet gave him fifty bucks to help him get through the week. That afternoon Lenny asked me if he could borrow ten dollars. I said, I thought Chet gave you fifty? He said, yeah that was at lunch. (laughter) I asked him what happened and he said that he had needed to get his shoes shined and the last guy he saw was downtown so he took a cab to the bus station.

Between the cab ride and the shoeshine his fifty bucks was gone. He didn’t worry about the things the rest of us worry about. He wasn’t thinking about anything except getting his shoes shined, not how do I make the money last. I told somebody once, “Lenny is like a national treasure. We should hire a park ranger to follow him around and take care of him.” (laughter)

I’ll tell you what though; he was the sweetest guy you could ever know. My kids just loved him and when kids love someone that says it all.

Tell me the story about Lenny playing in Texas and the little girl that came up on stage.

Yes! I took him with me to a community college back in Dallas because I wanted everybody to hear him. That evening, I believe it was in the campus coffee shop where Lenny played. There was a small audience of about seventy-five people.

At one point he played “My Funny Valentine.” As he played he keep getting farther and farther out, it was the most spellbinding thing I had ever seen. When he finished nobody moved, nobody clapped, nobody coughed, nothing! The whole room had been hypnotized. He looked around and stood up, still nothing. Then a little girl about three years old ran up and hugged his leg and everyone started clapping. It took this little girl to break the spell.

All of us who knew him understood the kind of magic that was in the air, not a hundred percent of the time but when Lenny was at his best he was utterly captivating. He was one of the greatest artists who ever lived. To me it was like knowing Van Gogh.

Tell me more about your friendship with Tommy Emmanuel and working with him.

The first time we played together was at Kirk Sands booth during the Chet convention. We just hit it off. Tommy invited me over to Germany with him for a week so we worked up some tunes and played a few in his show. We were both surprised how quickly we agreed on things and how it should work. We both grew up listening and thinking about Chet, though neither one of us sound like that now. I think that common background helped us. Later we did a Christmas record together. It’s a lot of fun working on arrangements with him. Tommy is never in town more than a few days at a time so you start working on a Christmas record in February. Then by July you hope you can play them. All the while you are relying on Skype and iTunes and an occasional cup of coffee to put the arrangements together.

We are now working on an album of love songs. Our idea is to record love songs but not all romance songs. I don’t know what it’s going to be called, but we’re about a third of the way into recording it and half way through arranging it. We are trying to cover different styles and time periods. We hope to finish it this year but neither of us want to finish before it’s ready.

Do you think there is a common thread between Chet, Jerry, Lenny and Tommy?

Well, I don’t think any of us would be doing what we are doing without Merle Travis and all the Kentucky guys, that’s a thread without a doubt. As musicians they were all individuals but they never saw limitations in the guitar.

I’ve always enjoyed the tune “My Little Waltz” that you wrote with Chet. It has a delicate music box quality. Tell me about writing and recording that piece with Chet.

That was the summer of 1976. We had just moved to Nashville. Chet called me and said he had started a tune and wanted me to help him finish it.

He played the A-section of “My Little Waltz” for me several times until I could play it... more or less. We played around with a few ideas that day but nothing was delighting us so I told Chet I’d like to work on it at home and show him what I had the next day.

At home, I kept playing the A-section because I wanted the B-section to sound like it belonged. And I wanted to keep the classical feel Chet had established. I was looking for something to contrast with the A-section that’s when I came up with the openstring, eighth-note phrases. Once I had a start, I could hear the rest in my head.

When I played him my B-section the next day, he liked it and learned it pretty quickly. Then we went looking for an intro. As I recall we just worked back and forth until we found what you hear on the recording.

Chet wanted to call it “My Little Waltz” because he had always liked “Petite Waltz” as a tune and a title. A few days after we wrote it, Chet had recorded it. Now it had an ending. Chet had some ideas for a second part so I went to his home studio and played along with his track while he gave me an idea of what he was looking for. He sang some lines and said, “something like that.”

I remember recording my part with my Kohno classical. Chet listened and said that my guitar sounded too good. He went back in his storage room and found a classical clunker... a refugee from a pawnshop. “Try this,” he said. That’s what you hear on the recording.

What was the process like to write with Chet?

Most of the tunes that Chet and I wrote together started with one of us having an idea. “East Tennessee Christmas” was like that. He had the melody to the A-section and the opening lyric, “East Tennessee Christmas, callin’ to me.” He knew he wanted a song he could play and sing.

On the lyrical side, we just talked our way through it. Like... what are you anticipating? That leads to shopping, decorating, wrapping, etc. When we got to the B-section, I observed, “Sometimes we get a White Christmas and sometimes we don’t.” Chet immediately said, “It might snow but don’t cha know that I don’t care.” I responded with, “It will be the best of Christmases if you are there.” We were on a roll. Now it’s about coming home and seeing someone you’ve missed. “Too long without you, too much on my own, East Tennessee Christmas, and I’m going home.”

We finished it up that evening at his house. I remember, Leona hearing us at work and stepping in to sing a line that extended the B-Section melodically and set up Chet’s instrumental. We made a cassette demo in Chet’s kitchen.

I left town for a session of the Puget Sound Guitar Workshop. When I got back, Chet had recorded our tune. He asked me to sing background vocals with him... just that once.

Tell me about other pieces you wrote with him and the story behind them.

When I heard Chet and George Benson were going to record, I started working on a tune with both of them in mind. I wrote the A-section around a 2-5-1 progression and was starting in on the B-section when I remembered Chet’s approach. I called him and we finished “Amanda From Barbados” together. Chet & George recorded it but most of the tracks from that project haven’t been released... yet.

Another time, I was playing Chet’s guitar while he was on the phone in his office. He heard me do something interesting so he put somebody on hold and said, “Tune the D-string down a fret.” That meant the open strings made an A9 chord. After he finished the conversation, he took the guitar and showed me how Lenny could play the blues with barre chords. Then I told him how the steel guitar player in my high-school Hawaiian band had one neck tuned to C9. We laughed and decided to write a Hawaiian blues tune. We worked for a little while and called it a day. When we re-convened, I had the A-section and Chet had the B-section to “Honolulu Blue.” I had written some fake lyrics to the A-section to give it a vocal feel. “Honolulu Blue, still missing you, I almost cried, when you said goodbye.”

Have you and Tommy written anything together? If not have you discussed the possibility?

Tommy and I have invested most of our time together coming up with duet arrangements. Recently, we started writing a tune. We worked on getting the chord progression and the form along with some key changes. Tommy recorded what we had so far on his iPhone and then headed for England. To be continued...

You now play the John Knowles model guitar built for you by Kirk Sand. Tell me about the design of this guitar and about working with Kirk on this special instrument.

Kirk and I have known each other and worked together over thirty years. He’s worked on all of my instruments and he’s watched me play. After I introduced him to Chet, I watched Kirk develop and build guitars for Chet, Jerry and Lenny.

Kirk and I used one of my Kohno guitars as a starting point for my JK Sand. I liked the brightness of the Sitka spruce top because I can get a warm sound without trying. I love the balance and sustain of the Kohno so Kirk knew to go for those qualities. He designed the heel of the neck so that it blends into the cutaway. You can feel the cutaway coming as you move up the neck. The scale is 650 mm and the fingerboard is two inches at the nut... both pretty standard for a classical. But there is a little less wood on the back of the neck and Kirk added a slight radius to the fingerboard. We decided on tall frets... based on our experiments with the Kohno.

We were trying out pickups when Rich Barbera sent Kirk a sample. We put it my guitar and I wouldn’t let him take it out. It really captures the dynamics of Kirk’s design. And I use John Buscarino’s Chameleon speakers with a Clarus amp from Acoustic Image.

I worked a lot with Clyde Kendrick over the years and really developed an ear and an approach for matching guitars with electronics. This combination makes me feel like making music.

What advice would you give to a young guitarist trying to find their way?

There is more than enough material out there these days... books, videos, etc. You can learn all the stuff you need to know. The question becomes, how are you going to put that stuff to work.

I think all of us learn from our heroes. They inspire us. But at a certain point, it is important to discover and develop your own voice. I remember hearing Les Paul ask, “If your mother heard you on the radio, would she know it was you?”

I am not sure that I convinced anyone, but it felt good to me

Your voice includes your touch... the sound you make. It also includes the music you choose to play... whether you write it or arrange it as well as your relationship with the listener. The listener can tell if you are authentic. You need the desire to reach the listener because you have something important to say and that their lives might be richer for it.

It may be a heavy question but how would you like to be remembered both as a person and a musician?

Whew! I remember when I left my job as a research scientist at Texas Instruments. A lot of my friends thought I was crazy. I thought they would understand if I told them that I felt the universe needed me to be a musician more than it needed me to be a scientist. I am not sure that I convinced anyone, but it felt good to me... to hear my voice say it out loud. So that is what I am doing. I’m making music because it is deeply important to me.

It is also important that I share what I have learned. Throughout my life, other musicians have been very generous towards me... with their time and their wisdom. I can express my gratitude by being generous toward others.

The music passes through us. We play it and we pass it on...